Diferencia entre revisiones de «Memoirs of the 3rd Anniversary»

De iMMAP-Colombia Wiki

| (No se muestran 32 ediciones intermedias del mismo usuario) | |||

| Línea 1: | Línea 1: | ||

| − | [[Image:Portada 1.1.jpg| | + | [[Image:Portada 1.1.jpg|400x550px]] <br> |

<br> | <br> | ||

| Línea 109: | Línea 109: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | = First Day Presentations = | + | == First Day Presentations == |

The following are syntheses of the presentations delivered<br>by nationally recognized experts during the first day of the<br>conference. These presentations addressed three overarching<br>themes: challenges posed by the war economy, challenges in<br>the framework of land and territory restitution initiatives in the<br>context of the armed conflict, and challenges for humanitarian<br>action. | The following are syntheses of the presentations delivered<br>by nationally recognized experts during the first day of the<br>conference. These presentations addressed three overarching<br>themes: challenges posed by the war economy, challenges in<br>the framework of land and territory restitution initiatives in the<br>context of the armed conflict, and challenges for humanitarian<br>action. | ||

| − | ''' María José Torres, Head of Office – OCHA; Camilo Ramírez,<br>Researcher of the Observatory of Reality – SNPS''' This two-day event had the objective of posing the concerns<br>of HSI member organizations regarding new conflict dynamics<br>that have emerged in connection with the Victims’ Law and Land<br>Restitution process, the political economy of conflict, and the<br>role of humanitarian action in this context. Through specific case<br>studies, we sought to unite and capitalize on the experience and<br>vision from diverse regions. Towards this end, the HSI Board of<br>Directors delegated the leadership of this event to Consultoría<br>para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento (CODHES),<br>Pastoral Social and OCHA. In addition, the event counted with<br>the valuable support of numerous organizations, even outside<br>the HSI membership, such as Defensoría del Pueblo, MAPP-OES,<br>UNDP, the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), Solidarity<br>International, UNHCR, and the Canadian Embassy. | + | ''' María José Torres, Head of Office – OCHA; Camilo Ramírez,<br>Researcher of the Observatory of Reality – SNPS''' |

| + | |||

| + | This two-day event had the objective of posing the concerns<br>of HSI member organizations regarding new conflict dynamics<br>that have emerged in connection with the Victims’ Law and Land<br>Restitution process, the political economy of conflict, and the<br>role of humanitarian action in this context. Through specific case<br>studies, we sought to unite and capitalize on the experience and<br>vision from diverse regions. Towards this end, the HSI Board of<br>Directors delegated the leadership of this event to Consultoría<br>para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento (CODHES),<br>Pastoral Social and OCHA. In addition, the event counted with<br>the valuable support of numerous organizations, even outside<br>the HSI membership, such as Defensoría del Pueblo, MAPP-OES,<br>UNDP, the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), Solidarity<br>International, UNHCR, and the Canadian Embassy. | ||

As a result, the present Memoirs of the 3rd Anniversary of<br>HSI offer a collaborative perspective of humanitarian issues in<br>Colombia through thirteen regional case studies, key actors<br>and factors of the armed conflict, and crucial vulnerabilities and<br>capacities of humanitarian action. This effort is aimed not only<br>at contributing to the academic and public debate on relevant<br>humanitarian issues, but also at supporting the real capacities of<br>humanitarian actors.<br> | As a result, the present Memoirs of the 3rd Anniversary of<br>HSI offer a collaborative perspective of humanitarian issues in<br>Colombia through thirteen regional case studies, key actors<br>and factors of the armed conflict, and crucial vulnerabilities and<br>capacities of humanitarian action. This effort is aimed not only<br>at contributing to the academic and public debate on relevant<br>humanitarian issues, but also at supporting the real capacities of<br>humanitarian actors.<br> | ||

| Línea 129: | Línea 131: | ||

'''Synthesis''': Corruption in the region operates through<br>a relationship between provision of public funds to narcoparamilitary<br>groups (parallel financial system or “Cooperatives”);<br>movement of AUC’s territorial control from poorer to richer<br>departments to increase capture of public funds (“Parapolítica”);<br>and “franchise adjudication” for drug trafficking routes. For<br>example, funds assigned to several hospitals, including Materno<br>Infantil de la Soledad, San Cristóbal de Siena, and San Juan de<br>Dios de Magangue, were being diverted to the paramilitaries. In<br>Mr. Pedraza’s words, “funds for life were being used for death”.<br>The presenter’s research geo-references the expansion of AUC’s<br>territorial presence from 1995 to encompass the virtually all of<br>the Atlantic Coast in 2003. The AUC’s plan was to co-opt part of<br>the state’s monopoly over security and the use of force, taxation,<br>and energy sources. | '''Synthesis''': Corruption in the region operates through<br>a relationship between provision of public funds to narcoparamilitary<br>groups (parallel financial system or “Cooperatives”);<br>movement of AUC’s territorial control from poorer to richer<br>departments to increase capture of public funds (“Parapolítica”);<br>and “franchise adjudication” for drug trafficking routes. For<br>example, funds assigned to several hospitals, including Materno<br>Infantil de la Soledad, San Cristóbal de Siena, and San Juan de<br>Dios de Magangue, were being diverted to the paramilitaries. In<br>Mr. Pedraza’s words, “funds for life were being used for death”.<br>The presenter’s research geo-references the expansion of AUC’s<br>territorial presence from 1995 to encompass the virtually all of<br>the Atlantic Coast in 2003. The AUC’s plan was to co-opt part of<br>the state’s monopoly over security and the use of force, taxation,<br>and energy sources. | ||

| − | '''Juan Enrique Martínez – Defensoría del Pueblo<br>''' | + | '''Juan Enrique Martínez – Defensoría del Pueblo<br>''' |

| + | |||

| + | '''Synthesis: '''In the government’s rush to turn mining into an<br>engine for national development, it has pressed small-scale artisan<br>miners to adapt to industrial mining. For example, mercury use<br>among gold miners is being prohibited and replaced with cyanide,<br>which is biodegradable but is also highly toxic and harmful to the<br>health of miners, especially children. Additionally, armed actors<br>are exploiting mining for money laundering and extortion. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Víctor Negrete – Centro de Estudios Sociales y Políticos,<br>Universidad del Sinú en Córdoba''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Synthesis''': As a resource rich department, with three mountain<br>ranges, a hydroelectric plant, and iron nickel mines, Córdoba is a<br>strategic region for drug production and trafficking, which helps<br>fuel the armed conflict. Córdoba hosts various non-state armed<br>groups, “parapolitical” actors and foreign investment, and merges<br>the broader conflict dynamics of Urabá, southern Bolivar, and la<br>Mojana. Just 5.4 per cent of the land is devoted to agriculture, but<br>it contributes more to the GDP than the 64 per cent of the land<br>devoted to extensive cattle ranching, highlighting the inadequacy<br>of Córdoba’s development model. The introduction of non-native<br>trees for wood production, biofuel crops and GMOs (genetically<br>modified organisms, such as corn and cotton strains from Monsanto)<br>is affecting biodiversity and has yet to yield tangible social benefits.<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Panel 2. Challenges in the framework of land<br>and territory restitution initiatives in the context<br> of the armed conflict == | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Moderator:''' Camilo Ramírez – SNPS | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> '''Carlos Chica, C''''''ommunications Coordinator - United Nations<br>Development Programme (UNDP)''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Title: '''Rural Colombia: Reasons for Hope | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Synthesis:''' The presentation reviewed recurrent structural<br>crises on the basis of UNDP’s National Human Development<br>Report 2011. These crises result from an economic model that is<br>adverse to human development, a rigid land structure, and the<br>persistence of an unfair, undemocratic and exclusive rural order.<br>Historically, the state has neglected and been disarticulated from<br>the rural sector, focusing instead on industrial urban development.<br>The Report recommends a transformative rural reform aimed at<br>eradicating poverty, overcoming rural conflicts, and modifying<br>the agrarian structure. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''William Quintero, DDR Manager – MAPP-OAS''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Synthesis:''' The presenter commended the Victims’ Law and<br>the Land Restitution process for constituting significant public<br>policy advances and prioritising victims. However, insecurity and<br>community distrust towards government institutions constitute<br>critical challenges. Ongoing displacements, the re-victimization<br>of communities that are undergoing land restitution, and the<br>lack of clarity among government institutions on their roles are<br>also concerns. The use of front men to acquire lands, violently<br>or otherwise, poses further obstacles, particularly in areas where<br>post-demobilization groups are exerting force to protect illegally<br>seized properties.<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> ''1 “Rural Colombia: Reasons for Hope”, National Report on Human Development, UNDP,<br>Colombia, 2011.''<br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Ivonne Moreno, Planning Coordinator of the Land Restitution<br>Program – Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Title:''' Land Restitution – Victims’ Law and Land Restitution,<br>Law 1448 of 2011 | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Synthesis:''' Forced displacement has historically been central<br>to the territorial configuration of Colombia. Approximately 55<br>per cent of IDPs abandoned or were dispossessed of their land,<br>resulting in 5.5 million ha (or 11 per cent of Colombia’s arable land)<br>in abandoned and now illegally held land. The Land Restitution<br>process seeks to guarantee the right of victims to have their<br>land properly titled and returned, and improve socio-economic<br>conditions in the rural sector. The government recognizes<br>significant challenges and risks in this process, and developed a<br>strategy to mitigate these by strengthening civil society. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Adriana Buchelli, Protection Officer - UNHCR''' '''Title:''' Challenges of Territory and Land Restitution Initiatives | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Synthesis''': Territory and land restitution initiatives face serious<br>challenges, particularly due to the ongoing-armed conflict. Special<br>attention must be paid to the risks of restitution processes,<br>and greater institutional capacity and protection measures are<br>required to mitigate them. In addition to protection measures<br>by the state, community development and protection networks<br>play an important role. Coordination between institutional and<br>international community initiatives should be enhanced. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> '''Carlos Andrés Ramírez, Representative - Comisión de<br>la Sociedad Civil Vallecaucana para el Seguimiento a la<br>implementación de la Ley de Atención de Victimas 1448 de 2011 /<br>Corporación Nuevo Arcoíris''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> '''Synthesis''': Civil society was late to the development of Victims’<br>Law, and has had limited representation in its implementation.2<br>Instead of viewing the law as a favor to victims, their rights to<br>justice, non-repetition and reparation must be guaranteed to<br>ensure community empowerment. The greatest challenge for<br>collective reparations is their sustainability (fulfilling guarantees<br>of non-repetition) and considering the multiplicity of parties<br>involved. In analysing the feasibility of implementation, we must<br>also take into account the corrosive role of drug trafficking in<br>public policy as evidenced in the political violence prior to the 2011<br>local elections. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Panel 3. Challenges for Humanitarian Action == | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Moderator''': Gustavo Salazar – Universidad Javeriana | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''María José Torres, Head of Office – OCHA''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> '''Synthesis:''' Key challenges in the implementation of<br>Humanitarian Action include the invisibility of civilian needs;<br>the placement of checkpoints by armed actors, including<br>post-demobilization groups without clear political objectives<br>(denominated by the government as criminal bands, or “BACRIM”<br>for the Spanish acronym); presence of APM/UXO; assistance<br>for emergency prevention and mitigation; and discrimination<br>against vulnerable populations and subgroups. Implementation<br>of the land restitution process in the midst of an active conflict<br>may obscure ongoing humanitarian issues, including forced<br>displacement, massacres, and humanitarian access. Moreover,<br>the transformation of the government agency Acción Social<br>threatens to de-prioritise humanitarian assistance within the<br>agenda of Victims’ Law. Moreover, as 50 per cent of Colombia’s<br>rural population lives in zones of yellow and red alert for APM/<br>UXO presence, the restitution in these zones may result in more<br>victims of these devices. Greater CSR among economic engines<br>is important in order to address the impacts on natural resources<br>and the environment, as well as social conflicts and the armed<br>conflict. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''2 CODHES makes a similar comment, stressing that the current version of Victims’ Law<br>did not undergo public consultations in order to incorporate proposals from victims’<br>groups. “De la seguridad a la prosperidad democrática en medio del conflicto”, CODHES<br>Informa, Número 78, Bogotá, 19 September 2011, p. 22.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Giovanny Cruz, National Coordinator of Humanitarian and<br>Emergency Affairs – World Vision''' '''Synthesis:''' The Victims’ Law must go beyond mere assistance in<br>order to facilitate life with dignity and engage civil society in early<br>recovery processes within a broader framework of humanitarian<br>action. Humanitarian organizations have a key role to play in<br>listening to communities and learning from them, in order to<br>help fortify existing capacities. Given that civil society offers the<br>first response to emergencies, humanitarian actors must build a<br>strong alliance with it. Finally, it is imperative to create academic<br>programs in order to further professionalise officials delivering<br>humanitarian assistance. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Luisa Bacca, Protection Officer – UNHCR, Nariño''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Title:''' Permanent Humanitarian Mission in the Awá’s Indigenous<br>Territory | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Authors''': Protection Cluster - Gender Working Group - Nariño | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Synthesis: '''The territory of the Awá indigenous people is located<br>in the departments of Nariño and Putumayo. This community<br>faces the threat of cultural and physical extermination due to the<br>ongoing-armed conflict, the lack of governance and institutional<br>support, and structural poverty. The Permanent Mission is<br>composed by UN agencies and international NGOs, and aims to<br>provide protection through their presence and by advocating for<br>the rights of the Awá people. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Ángela Sánchez, Coordinator of Southwestern Office – Oxfam'''<br>'''Title''': Documentation of the experience of Gender<br>Differentiated Approach in Nariño department<br>'''Authors''': Gender Working Group - Local Humanitarian Team –<br>Nariño | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Synthesis:''' Women and their families in Nariño face special risks<br>posed by the armed conflict and a complex humanitarian context.<br>Some of these include individual and massive displacement,<br>child recruitment, pressure regarding illicit crop cultivation and<br>eradication, APM/UXO, confinement and mobility restrictions,<br>direct attacks and SGBV. The main objectives of the Gender Working<br>Group are to: mainstream the gender approach of humanitarian and<br>development projects; promote the implementation of effective<br>protection mechanisms for women; advocate for the assistance<br>HIV victims; further the development of new masculinities; and<br>communicate experiences of applying a gender differentiated<br>approach with indigenous and afro-descendent women in Nariño. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Imagen 3.jpg|399x549px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| − | + | <br> | |

| + | = Regional Surveys = | ||

| + | [[Image:Regional Surveys.jpg|410x560px]] | ||

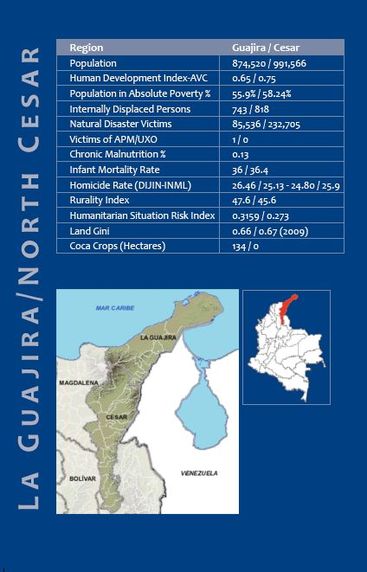

| − | + | == I. LA GUAJIRA/NORTH CESAR<ref /> == | |

| − | + | [[Image:La Guajira-Nort Cesar.jpg|422x572px|421.5x571.5px]] | |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | Confrontation among non-state armed groups in the area is<br>related to control of drug trafficking routes, taking advantage<br>of ports in La Guajira and sparse border that both La Guajira<br>and northern Cesar share with Venezuela. According to Gerson<br>Arias, paramilitarism consolidated in the region during the 1990s<br>due to the tolerance of illicit activities by the Wayúu and other<br>local communities, the continuity of contraband and other illicit<br>activities by private armed actors, and the support or inaction of<br>civil and military authorities.2 Some mining executives came to<br>justify and support these structures due to attacks by ELN on their<br>infrastructure, hostile environment, and limited State protection.3<br>Post-demobilization groups are increasing their presence, partly<br>by rearming demobilized paramilitaries.<br>Armed groups have engaged in relatively selective violence<br>throughout the region, and crimes such as human trafficking,<br>small-scale drug trafficking and money laundering are key<br>concerns. The institutional capacity to investigate and prosecute<br>crimes by non-state armed groups and guarantee the protection<br>of civilians needs to be reinforced in order to combat impunity.4<br>Profound social distrust towards the public and private<br>sectors hinders the implementation of public policies and social<br>programs. This is exacerbated by the efforts of some officials to<br>discredit victims and obstruct justice, as was evidenced in the<br>proceedings regarding the killing of five civilians in June 2011, by<br>members of the Army in Cesar.5 | ||

| − | + | Since the 1980s, 70,000 indigenous people have been displaced<br>in La Guajira and Cesar due to mining activities, particularly those<br>of El Cerrejón, the largest coal mine in Colombia.6 Also, mining<br>exploitation by Drummond in Jagua de Ibirico provoked a series<br>of displacements and illegal land appropriations, including in the<br>townships of Mechoacán and Prado. Similarly, there appear to<br>be forced displacements in Pueblo Bello and Valledupar, and in<br>neighbouring Sierra Nevada de San Marta. Carbon mining has<br>contaminated Rancherías River, the most important in Guajira,<br>triggering diarrhea and rashes among indigenous people who<br>depend on it.7 Repopulation strategies have resulted in complex<br>situations, given the leadership of armed groups and mafias<br>that have coopted processes through political infiltration and<br>corruption. Consequently, some displacements between Dibulla<br>and Riohacha, attributed to the post-demobilization groups<br>Rastrojos and Urabeños, have gone unreported. In the El Copey<br>zone, displacements and forced sales have taken place for palm<br>cultivation. Combats between the army and the FARC have<br>resulted in three massive displacements in El Perijá.<br>Mining expansion projects throughout the region, strip mining<br>in Perijá Mountains and the diversion of Ranchería River for coal<br>exploration have all had a significantly negative environmental<br>impact and enhance the local population’s vulnerability to<br>disasters of natural origin.<br>Civil society is reportedly becoming weaker and more<br>fragmented, affecting most local ethnicities and inhabitants.<br>Moreover, illegal surveillance, threats against and murders of<br>union and community leaders in Cesar is hindering local capacity<br>to provide social mobilization and advocacy.8 Land use is heavily<br>determined by the territorial control of non-state armed groups,<br>which is currently being disputed in urban areas of central and<br>northern Cesar. A non-state armed group, calling itself “Wayúu<br>counter-insurgency front of Alta Guajira”,9 is responsible for a<br>series of massacres10 and is feeding inter-ethnic conflicts tied to<br>retaliation traditions.<br>The interaction between paramilitary networks and politicians<br>(“parapolítica”) persists in La Guajira without the visibility and<br>political restructuring that took place elsewhere in the country.<br>Traditional political networks remain unaltered and illegal<br>networks continue to operate under the control of political elite<br>families, thus hindering human rights work. In contrast to other<br>regions, Cesar experienced a change in political power and the<br>victims’ agenda became a priority thanks to the pressure placed by<br>civil society organizations. Nevertheless, effective sustainability<br>and a long-term strategy do not appear feasible.<br>Despite the existence of significant humanitarian crises,<br>regional experts stress the very limited presence of humanitarian<br>actors in the region. | |

| − | + | <br> | |

| − | <br> | + | ''1. While the regional statistics and map refer to the departments of Guajira and Cesar<br>as a whole, the information below focuses on conflict and humanitarian dynamics in<br>Guajira and the northern region of Cesar.<br>2. Arias, Gerson, “Pasado y Presente del entorno de seguridad en La Guajira”,<br>Fundación Ideas para la Paz and VerdadAbierta.com, Bogotá, 27 October 2010,<br>Presentation at Event.<br>3. Reyes Posada, Alejandro. 2008. Guerreros y Campesinos: El despojo de la tierra en<br>Colombia. Bogotá: Fescol, Grupo Editorial Norma, p. 208.<br>4. As asserted by UNHCHR, impunity is a “structural problem affecting the full<br>enjoyment of rights.” “Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human<br>Rights on the situation of human rights in Colombia”, UNHCHR, 31 January 2012.<br>5. Some Army officers continue to deny extrajudicial executions, including “false<br>positives”, instead discrediting the justice system and victims. UNHCHR, 2012, p. 8.<br>6. “Minería en Colombia: ¿a qué precio?, Boletín informativo no. 18 PBI Colombia”,<br>Peace Brigades International, Bogotá, November 2011, p. 32<br>7. Ibid.<br>8. UNHCHR, 2012, p. 5.<br>9. Notorious paramilitary Jorge 40 allied with José María Barros Ipuana and José María<br>Gómez to establish this front, but resistance by traditional indigenous structures has<br>been fierce and sometimes violent. “Dinámica Reciente de la Confrontación Armada<br>en la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta”, Observatorio de Derechos Humanos de la<br>Vicepresidencia, February 2006.<br>10. The massacre on April 18, 2004 in Bahía Portete (Guajira) was a targeted attack<br>on women with profound implications on a relatively populous, but historically<br>threatened, indigenous minority. It simultaneously exemplifies the highly functional<br>use of violence against women, and the role of deep-seated institutional and societal<br>discrimination against marginalized communities. The massacre not only threatened<br>the historical, cultural and mythical patrimony of the community, but also its ethnic<br>survival. “La Masacre de Bahía Portete: Mujeres Wayuu en la mira”, CNRR, Bogotá,<br>2010.''<br> |

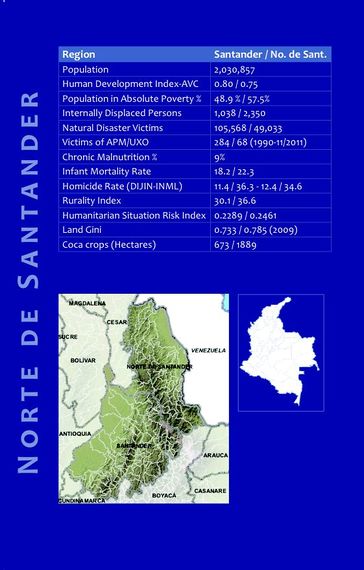

| − | + | == II. NORTE DE SANTANDER == | |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Image:Norte de Santander.jpg|420x570px]] | |

| + | <br>The Department has a geostrategic location, which has made it a key corridor for drug and human trafficking, as well as arms and fuel smuggling. The high presence of non-state armed groups and criminal organizations in the border areas create security risks that impact the civilian population and exacerbate humanitarian needs. Over the past two years there have been massacres, homicides, kidnappings and human trafficking throughout the zone.1<br>The end of the armed conflict in the region remains elusive, particularly taking into account the intensity of the armed conflict along the border with Venezuela. Non-state armed groups and criminal organizations have reportedly formed alliances to exploit drug trafficking. Manual drug crop eradication processes take place throughout the Catatumbo area of Norte de Santander, leading to constant protests, armed confrontations and an increase in the use of landmines. These events lead to displacement risk and affect local food security.2<br>Children and teens are vulnerable to recruitment by illegal armed groups, particularly in Catatumbo and the Cúcuta Metropolitan area, and prevention policies need to be further developed and implemented. There are two reports of threats by the FARC to recruit 7-year-old boys.3 There are periodic trainings and minors reportedly participate in isolated operations. The Motilón-Barí community is considered to be an indigenous community at high- risk due to the conflict.4 Another concern is human trafficking, as well as high SGBV and HIV/AIDS rates among IDPs. | ||

| + | <br>In 2010, armed actions increased to 62 reported events related to the armed conflict, compared to 47 in 2009. During 2010, 27 out of the 40 municipalities, representing 67.5 per cent of the Department, were affected by armed or violent actions related to conflict.5 According to the local NGO Progresar, there were 60 reported cases of forced disappearance in 2010, 90 per cent of which were concentrated in the municipalities of Cúcuta and Villa del Rosario.6 Since 2008, Human Rights and IDP organization leaders have reported numerous threats.7 Non-state armed groups have threatened former government employees and candidates to public office.<br>The threat of displacement is mostly individual, though there are risks of mass displacement in areas such as Catatumbo. In 2010, the accumulated number of IDPs reached 79,851 expelled and 101,654 received. There is an under-registry, with a high percentage of ‘non-inclusion’ of IDP declarations on the part of former Acción Social, including non-registry of “inter-vereda”<br>28 (rural displacement within a municipality) or inter-urban displacement, which cannot be declared according to Law 387 or are invisible; flight to other regions or across the Venezuelan border.<br>The 2010-2011 rainy season left a total of 61,746 persons affected in Norte de Santander, and caused flooding and landslides in 80 per cent of Department. The Gramalote municipality was entirely destroyed and must be re-located due to geological fissures. During 2011, the local authorities reported 3,321 new families affected by the rainy season. While adults consumed three daily food rations, children consumed just two.8 The WFP delivered 8,249 food rations to 2,749 families, 13,745 people. The National Response Organization Colombia Humanitaria has given monetary resources to respond to the needs identified on food, shelter and sanitation.<br>The rainy season also led to the collapse of 71 per cent (1,017 of 1,436km of roads) of the secondary road system, including the road infrastructure connecting the capital, Cúcuta. This resulted not only in the isolation of the capital, but also in constraints for humanitarian access.<br>APM/UXO presence also hinders access and mobility, not only for the local population, but also for humanitarian organizations. In 2010 there were 43 APM/UXO events, killing one civilian and 31 military personnel. The Department has among the top five numbers of victims of these devices in Colombia. The risk is exacerbated as guerrillas use these devices in their attempt to block the entrance of manual eradicators of coca crops in their zones of influence. | ||

| − | + | <br> | |

| − | '' | + | ''1. Information provided by regional field office, OCHA, May 2011.<br>2. Information provided by regional field office, OCHA, May 2011. <br>3. UNHCHR, 2012, p.14.<br>4. Information provided by regional field office, OCHA, May 2011.<br>5. Information provided by regional field office, OCHA, May 2011.<br>6. Report on Human Rights in Norte de Santander: Right to Life and Physical Integrity, National NGO Progresar, 2012.<br>7. Special Report on the increase of “False Positives”, Centro de Investigación y Educación Popular (CINEP), 2011.<br>8. Report on Food Security, regional field office of the World Food Program, 2011.''<br><br> |

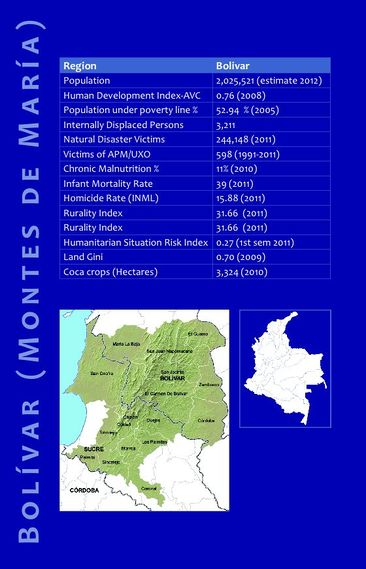

| + | == III. BOLIVAR (MONTES DE MARIA) == | ||

| + | [[Image:Bolivar Montes de Maria.jpg|420x570px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Montes de María has historically been treated as a “laboratory”, combining the implementation of the National Consolidation Plan, the Victims’ Law and Land Restitution, rural resident reserve and rural development areas. The zone also presents all major actors of the armed conflict, each with a territorial control exercised over a certain part of society.1<br>The military is building capacity among youth for the prevention of forced recruitment and child exploitation, as well organizing communities around the land restitution process. It is of concern that the government remains silent regarding numerous IHL infractions and IHRL violations in the zone.<br>Despite highly visible public policies in Montes de María, massive land purchases2 and the “drop-by-drop” displacement phenomenon are still ongoing, though they are often not officially reported and thus “invisible”. Overall, there were an estimated 240 persons displaced from the region in 2010.3<br>Local capacities have been strengthened thanks to the establishment of a rural resident reserve zone (community self-protection process) with an Impulse Committee and Rural resident Reserve Board, which is involved in resolving boundary disputes between rural residents. In addition to the network of victims’ leaders, there are strong networks of civil society organizations. This was illustrated by the protests that managed to influence public policies in defense of their rights. However, it is troubling that non-state armed groups have confronted these civil society networks, resulting in the killing of 50 persons in the zone during 2010.4<br>Though rural resident reserve zones exist as a strategy to curb mono-crop cultivation and massive land acquisition, mega- projects and plans for the exploitation of natural resources continue advancing.5 Even while rural resident reserve and rural development zones are promoted, large plots of land are being distributed to extractive industries and monocultures, threatening the territorial and social integrity of the local communities. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''1. Presence of new NSAGs, Urabeños, ERPAC (formally surrendered to justice on December 2011) and Paisas, has been demonstrated in 9 of the 15 municipalities of Montes de María. Another such group, Rastrojos, was detected in San Onofre. The FARC retreated to remote areas after the death of alias ‘Martín Caballero’ in October 2007, but they are now reorganising.<br>2. Given the perpetuation of conflict dynamics in the zone, these purchases are often enforced through varying levels of intimidation violence, or exploit conflict- induced drops in land values to accumulate real estate far below its “real value”.<br>3. Information provided by network of victims’ leaders.<br>4. Assassinations have concentrated in the municipalities of San Onofre, María Labaja, El Carmen de Bolívar, Ovejas, and San Jacinto. UNHCHR, 2012, p. 5.<br>5. Examples of this include the transversal highway from the west and oil exploitation in Tolú Viejo.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

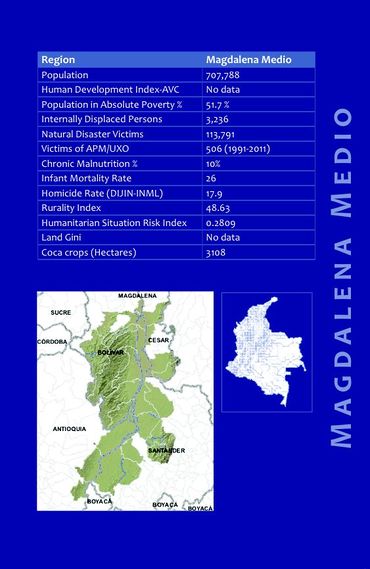

| + | == IV. MAGDALENA MEDIO == | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Magdalena Medio.jpg|420x570px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

| − | + | The region constitutes a strategic corridor for drug trafficking, with numerous key routes. It also concentrates significant coca crops, particularly in parts of Antioquia and southern Bolivar.1 The presence of non-food agribusiness, such as palm and mining, generates a series of social conflicts, particularly due to the confrontation and competition over land uses.<br>Both the FARC and ELN have historically held a strong presence in the region, but recent confrontations have been rare. Since the 1960s, the FARC has been present in southern Magdalena Medio, including not only rural areas, but also the metropolitan areas of Barrancabermeja and Bucaramanga.2 To cover their retreat from some areas, the FARC has planted APM in the municipality of Carmén de Chucurí and the township of El Toboso (Santander), where de-mining operations are taking place.3<br>The ELN has concentrated in northern Magdalena Medio, especially in the junction between southern Cesar and Santander departments, and southern Bolivar (the mountain range of San Lucas has been a historic bastion for the group).4<br>The region was a key landscape of paramilitary consolidation since the 1980’s, due to the support of some large landholders, businesspersons and cattle ranchers, who sought to counteract the pressure from guerrillas, as well as rural resident organizations mobilizing around land issues.5<br>Since the 1990’s, there have been a series of rural resident mobilizations against paramilitarism and proposals for citizen assemblies for territorial ordering, highlighting a high degree of community organization.6 In August 2011, rural resident, afro- descendant and indigenous community members gathered in Barrancabermeja for the event “Dialogue is the Route”, which pressed for humanitarian accords and a negotiated solution for the armed conflict.7<br>During recent years, post-demobilization groups, chiefly Urabeños, Águilas Negras and Rastrojos, have played a role in the continuation of the armed conflict in the region.8 These groups have sought to control coca cultivation zones and drug trafficking routes, and have relied on licit and illicit activities, including contraband, gold mining and extortion, in order to finance their operations.9<br>In addition to commercial activities, these groups have engaged in serious lbreaches of human rights and humanitarian law, including forced displacement, threats against community leaders and organizations, and forced recruitment.10 Demobilized<br>paramilitaries and minors have been pressed, sometimes by force, to join these new groups,11 thus undermining the reintegration process. According to NGO Corporación Compromiso, during the first six months of 2011, 49 cases of serious human rights violations, 38 of socio-political violence, and 12 of humanitarian law violations, were registered throughout the department of Santander (part of which forms part of Magdalena Medio).12 Of the serious human rights violations, post-demobilization groups perpetrated 90 per cent.13 | |

Revisión actual del 16:51 11 jul 2012

These Memoirs were developed by the Humanitarian Studies Institute

allies. Compiled and edited by David Alejandro Schoeller-Díaz. Maps

and data provided by the United Nations Office for the Coordination

of Humanitarian Affairs UNOCHA – Colombia.

The HSI was established in 2008, with the objective of creating links

between Universities, NGOs and UN System Agencies, given the

demonstrated potential for research and training that exists among

local actors in order to improve quality of Humanitarian Action.

These Memoirs can be downloaded from the HSI Website at:

www.colombiassh.org/reh/memoirs3anniv

The Humanitarian Studies Institute (HSI) 2012.

Cover page photo: La Calle sonríe by Fabián Garzón Bustos

Interior photo: Atrás del matorral by Mario Barrero

1st Humanitarian Photography Contest.

Photo stream available in: http://bit.ly/McGA1W

Suggested citation:

Humanitarian Studies Institute (HSI) (2012). 1st Regional Conference.

Challenges of the Conflict in Colombia. 3 and 4 November 2011.

Bogotá: HSI.

Feedbacks and comments are welcome, and should be sent to:

iehinternacional@gmail.com

The Humanitarian Studies Institute would like to express its

gratitude for the financial support of the Canada Fund for Local

Initiatives (CFLI)

On the part of the Office for the Coordination of

Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), I would like to congratulate

the Humanitarian Studies Institute upon the celebration

of its 3rd Anniversary. HSI has been an important initiative working

towards the integration of humanitarian actors with academics

across Colombia in the areas of training, advocacy and research.

These Memoirs compile the results of a meeting of experts from

regions throughout Colombia, including NGO workers, public

officials from the Ombudsman’s Office, Agency personnel and

researchers, who came together to share their experiences in the

field. These types of meetings are invaluable for the humanitarian

community in Colombia, where the humanitarian situation

frequently tends to be out of public view, and opportunities

to share experiences widely are few. We sincerely hope that

these types of efforts will continue on the part of HSI and the

participants in the event in order to help save lives and reduce

the suffering of millions of Colombians who face the difficulties of

the country’s internal armed conflict and the effects of frequent

natural disasters.

With best wishes for continuing success,

María José Torres

Head of Office

Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)

Colombia, Technical Secretariat of the Humanitarian Studies

Institute

So… what’s next?

Many efforts are underway to address, confront and transform

the conflict in Colombia. From the highly publicized institutional

ones to those that occur almost invisibly in neighborhoods, villages

and communities aimed at improving coexistence between

neighbors. Others, from diverse civil society sectors, seek to position

their concerns and perspectives in the public arena in order to

mobilize community groups and affect policy. Unfortunately, many

efforts of this type are unknown or invisible simply because they

don’t occur in the epicenter of national decision-making, don’t fit in

the agendas of those who may finance them, or aren’t documented

and shared with the community, in our case, the humanitarian one.

In this context, these Memoirs, consolidated by HSI with much

effort, are one more contribution to advance the aspirations of

the Colombian people for a transformation of the armed conflict.

But how do these Memoirs contribute? And from here, what

might happen? I just want to note three issues that motivated this

gathering of speakers, stories and analysis. The discussion on these

issues may spur a reflection on our institutional practices, and thus

shine light on our future work.

In the first place, these Memoirs stand as evidence. This term is in

such vogue in our context that its meaning is often eroded. With this

text, regional representatives, national and international analysts,

participants, researchers, compilers, and all the collaborators of this

event and its results have become witnesses of what happened and

also of what was affirmed and understood. It’s worth remembering

that these Memoirs emerged in a historical moment after eight years

during which the existence an armed conflict was denied. Though

we can’t say this is the only written material on these subjects in

the aftermath of such era of denial, we can affirm that it stands out

as the product of wide participation of civil society and communitybased

organizations. For HSI, the result is not only a reliable

resource, but also one worthy of systematization and distribution.

Being witnesses of this event better equips us to be more attentive

observers of what happens in the country, especially, as said before,

those things that receive limited attention in the epicenter and don’t

appear as often in the newspapers or newscasts, yet are daily bread

in the country’s periphery. An exercise like this sets a precedent for

more participatory and inclusive discussions.

In second place, the experience of the “Challenges of the Conflict

in Colombia” Conference reveals a shift driven by many sectors of

Colombian society. I’m speaking about the sense of unity reflected in

this two-day exercise, as well as many more compiling the analysis.

It’s important to note that this concept of unity does not equate

to homogeneity, but instead to a diversity of perspectives and

alternatives to approach the conflict in Colombia. Being a member of

an organization focused on children and with strong community ties,

I’ve recognized that participation is nonnegotiable and decisive to

change the culture, structures and practices of a society in crisis. For

HSI and its partners, it’s very important to recognize the institutions,

experts and interns of the humanitarian field. Nevertheless, such

recognition is more valuable if their work is strongly linked to the

base of the community, which on a day-to-day basis experiences the

limitations and vulnerabilities, risks more than others, suffers and

cries. Transposing this diversity of perspectives into the Memoirs

(for the most observant of the text) is a paramount commitment,

because a black-and-white portrayal of the world is intolerable for

those who learn to be inclusive and recognize the value of diverse

perspectives.

Finally, these Memoirs are meant to propel humanitarian

work by enriching our agenda. In many social research projects,

systematization exercises have fallen in the trap of further advancing

the positioning of institutional postures and/or publishing

achievements, rather than generating deep reflections, taking

advantage of lessons, and throwing them in a race to be learned

and incorporated into the practices of private and public life.

The analysis of actors, factors and vulnerabilities-capabilities,

as well as the accumulation of conclusions throughout the text,

is perhaps the most illustrative part. It’s useless to write only to

make history, only to leave a track, or show that one tried one’s

best. We write because a commitment is made for change and

transformation. When Colombians write their Memoirs, such as this

one, we are reading of ourselves in the present, but inevitably, as

we turn the pages, images emerge of how the future could turn,

whether we act or not. These Memoirs assert loudly that the conflict

in Colombia is and will remain what Colombians and their individual

and collective efforts want it to be. If we want something else, let

us learn from the past and present. For HSI, it’s clear that research

activities are a guide for progress and development, as long as their

findings are incorporated into everyday life in institutional practices,

and the work of social structures. Isn’t this a goal to pursue? Isn’t it

an agenda for our work and projection?

So... this is what follows, and on behalf of the Humanitarian

Studies Institute, we hope to have the intent, resources and

commitment of its members to: continue to create experiences like

this, contribute to a better understanding of humanitarian practice

in our context, and tirelessly explore possible ways to continue to

improve, change, transform what we have, into something better

for the country.

Eng. Giovanny Cruz G

National Coordinator of Humanitarian and Emergency Affairs

World Vision Colombia

President of the HSI Board of Directors

The Humanitarian Studies Institute (HSI) represents a joint

effort of United Nations agencies, NGOs and universities to

close the gap between the humanitarian community and

academia. To accomplish this goal, HSI works via three pillars:

advocacy, capacity building and research. As part of its advocacy

strategy, HSI promotes thematic events to examine humanitarian

crises, advance joint analysis of the humanitarian impact of

conflict-related issues and natural disasters, and disseminate the

framework for humanitarian action.

HSI expresses its sincere gratitude to the constructive

contributions of persons from academic institutions, civil society

organizations, NGOs and international organizations that joined

us from across Colombia. This includes organizations as varied

as Universidad del Sinú, Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana de

Montería, Oxfam, Corporación Nuevo Arcoíris, Comisión de Vida,

Justicia y Paz de la Arquidiócesis de Cali, Cocomasia, Diócesis

de Soacha, SAT functionaries of Defensoría del Pueblo, Fedes,

Programa de Desarrollo y Paz del César, and Fundación Montes

de María, among many others.

Sumario

Introduction

The First Regional Conference: Challenges of the Conflict in

Colombia was envisioned as an integrated discussion and joint

analysis on the conflict and humanitarian crises in Colombia, with

an emphasis on their territorial dimensions. Capitalizing on HSI’s

the three-year trajectory joining institutional efforts and bridging

gaps in knowledge, the Institute’s Board of Directors decided to

establish a national forum for open and critical discussion of these

issues. This forum invited representatives of the government,

civil society, academia, and humanitarian community to generate

a more inclusive, participatory and representative cross-sectoral

analysis.

The conference sought to capitalize on the shared knowledge

of key actors from different regions of Colombia, in order to bridge

the divide between institutions and sectors that are engaged in

the humanitarian field. The humanitarian field is especially suited

to benefit from enhanced dialogue and cooperation. Failure to do

so results in stagnation and critical gaps in knowledge, wasteful

overlaps and unattended needs, all of which can cost lives during

emergencies. Moreover, neglect of regions at the central level,

especially those that have been most hard-hit by violence and

crises, obscures the on-the-ground realities of an ongoing armed

conflict, and overlooks valuable knowledge, capacities and skills

needed to mitigate its humanitarian impact.

The two-day conference began with a day of three panel

discussions with nationally recognized experts. The first panel

concerned challenges of the war economy, and included

representatives of Acción al Día Colombia, Corporación Nuevo

Arcoiris, the Ombudsman’s Office, and Universidad del Sinú

in Córdoba. Panellists explored issues such as: the role of drug

trafficking and mining in fuelling armed groups and violent

conflict; the rapid emergence and consolidation of paramilitaries

throughout the Atlantic coast from the mid-1990s to the mid-

2000s; and the perverse effects of the development model in

exacerbating social and violent conflict in the department of

Córdoba.

The second panel addressed challenges of land restitution in the

context of an ongoing-armed conflict. Panellists represented the

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Mission of

the Organization of American States to Support the Peace Process

in Colombia (MAPP-OAS), the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural

Development, the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), and

the Comisión de la Sociedad Civil Vallecaucana para el Seguimiento

a la implementación de la Ley de Atención de Victimas 1448 de

2011. The discussion offered a critical examination of humanitarian

concerns and possible obstacles facing the implementation of the

land restitution process. Identified obstacles included: insecurity

and distrust of government institutions; informal land ownership;

limited civil society participation in drafting and implementing

the law; and the long-term task of boosting sustainable human

development in the rural sector.

In the last panel, representatives of the United Nations Office

for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), World Vision,

UNHCR and Oxfam reflected on the challenges for humanitarian

action. OCHA expressed concerns regarding confinement and

ongoing displacement, execution of land restitution amidst an

armed conflict, the need for CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility)

to protect environmental resources and vulnerable communities,

and the use of APM/UXO. Moving beyond strict operational

concerns, World Vision stressed the importance of life with

dignity, engaging civil society in emergency recovery, and the

commitment of the humanitarian community to its values and

principles to serve. Lastly, UNHCR and Oxfam presented their

work in protecting the Awá indigenous community in Nariño,

and positioning sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) as an

issue deserving independent consideration within humanitarian

projects, respectively.

The second day connected diverse national and regional

experts within three discussion groups, with the objective of

identifying key elements of the conflict in the participants’

respective regions. Identified elements included actors and

factors of the armed conflict; territorial reorganization through

mega-projects and exploitation of natural resources; and the

vulnerabilities, capacities and prospects of civilian populations in

each region represented.

Ultimately, this event was aimed not only at contributing to

the academic and public debate on relevant humanitarian issues,

but also supporting the real capacities of humanitarian actors.

It generated a joint regional diagnostic, which can be used as

a tool to understand humanitarian conditions in Colombia, as

well as facilitate the formulation of key public policy themes for

protection, comprehensive and sustainable peacebuilding, and

humanitarian standards.

First Day Presentations

The following are syntheses of the presentations delivered

by nationally recognized experts during the first day of the

conference. These presentations addressed three overarching

themes: challenges posed by the war economy, challenges in

the framework of land and territory restitution initiatives in the

context of the armed conflict, and challenges for humanitarian

action.

María José Torres, Head of Office – OCHA; Camilo Ramírez,

Researcher of the Observatory of Reality – SNPS

This two-day event had the objective of posing the concerns

of HSI member organizations regarding new conflict dynamics

that have emerged in connection with the Victims’ Law and Land

Restitution process, the political economy of conflict, and the

role of humanitarian action in this context. Through specific case

studies, we sought to unite and capitalize on the experience and

vision from diverse regions. Towards this end, the HSI Board of

Directors delegated the leadership of this event to Consultoría

para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento (CODHES),

Pastoral Social and OCHA. In addition, the event counted with

the valuable support of numerous organizations, even outside

the HSI membership, such as Defensoría del Pueblo, MAPP-OES,

UNDP, the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), Solidarity

International, UNHCR, and the Canadian Embassy.

As a result, the present Memoirs of the 3rd Anniversary of

HSI offer a collaborative perspective of humanitarian issues in

Colombia through thirteen regional case studies, key actors

and factors of the armed conflict, and crucial vulnerabilities and

capacities of humanitarian action. This effort is aimed not only

at contributing to the academic and public debate on relevant

humanitarian issues, but also at supporting the real capacities of

humanitarian actors.

Panel 1. Challenges posed by the War Economy

Moderator: Francisco Taborda - CODHES

Ricardo Vargas, Director of Acción Andina Colombia –

Transnational Institute (TNI)

Synthesis: Anti-drug policies in Colombia have succeeded

in reducing the coca leaf yield per hectare, and are being

internationally presented as a success case and best practice to

be followed by other countries. This is in part because the U.S.

has sought to promote south-south cooperation and reduce its

own burden in the war against drugs. Unmentioned regarding

the global war on drugs in Colombia are its negative impacts, as

evidenced by the direct correlation between violent events and

coca crop prevention and eradication policies. The role of nonstate

armed groups is key to drug trafficking. The presenter noted

with concern that the state has been relinquishing its control

over regions to private entities, and links persist between drug

trafficking and local, regional and national governments. Post

demobilization groups have been substituting the state in areas

where it’s absent, and control both legal and illegal activities,

beyond merely drug trafficking.

Hernán Pedraza, Analyst – Corporación Nuevo Arcoíris

Title: Corruption Levels along the Caribbean coast

Authors: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung In Colombia - FESCOL

Synthesis: Corruption in the region operates through

a relationship between provision of public funds to narcoparamilitary

groups (parallel financial system or “Cooperatives”);

movement of AUC’s territorial control from poorer to richer

departments to increase capture of public funds (“Parapolítica”);

and “franchise adjudication” for drug trafficking routes. For

example, funds assigned to several hospitals, including Materno

Infantil de la Soledad, San Cristóbal de Siena, and San Juan de

Dios de Magangue, were being diverted to the paramilitaries. In

Mr. Pedraza’s words, “funds for life were being used for death”.

The presenter’s research geo-references the expansion of AUC’s

territorial presence from 1995 to encompass the virtually all of

the Atlantic Coast in 2003. The AUC’s plan was to co-opt part of

the state’s monopoly over security and the use of force, taxation,

and energy sources.

Juan Enrique Martínez – Defensoría del Pueblo

Synthesis: In the government’s rush to turn mining into an

engine for national development, it has pressed small-scale artisan

miners to adapt to industrial mining. For example, mercury use

among gold miners is being prohibited and replaced with cyanide,

which is biodegradable but is also highly toxic and harmful to the

health of miners, especially children. Additionally, armed actors

are exploiting mining for money laundering and extortion.

Víctor Negrete – Centro de Estudios Sociales y Políticos,

Universidad del Sinú en Córdoba

Synthesis: As a resource rich department, with three mountain

ranges, a hydroelectric plant, and iron nickel mines, Córdoba is a

strategic region for drug production and trafficking, which helps

fuel the armed conflict. Córdoba hosts various non-state armed

groups, “parapolitical” actors and foreign investment, and merges

the broader conflict dynamics of Urabá, southern Bolivar, and la

Mojana. Just 5.4 per cent of the land is devoted to agriculture, but

it contributes more to the GDP than the 64 per cent of the land

devoted to extensive cattle ranching, highlighting the inadequacy

of Córdoba’s development model. The introduction of non-native

trees for wood production, biofuel crops and GMOs (genetically

modified organisms, such as corn and cotton strains from Monsanto)

is affecting biodiversity and has yet to yield tangible social benefits.

Panel 2. Challenges in the framework of land

and territory restitution initiatives in the context

of the armed conflict

Moderator: Camilo Ramírez – SNPS

Carlos Chica, C'ommunications Coordinator - United Nations

Development Programme (UNDP)'

Title: Rural Colombia: Reasons for Hope

Synthesis: The presentation reviewed recurrent structural

crises on the basis of UNDP’s National Human Development

Report 2011. These crises result from an economic model that is

adverse to human development, a rigid land structure, and the

persistence of an unfair, undemocratic and exclusive rural order.

Historically, the state has neglected and been disarticulated from

the rural sector, focusing instead on industrial urban development.

The Report recommends a transformative rural reform aimed at

eradicating poverty, overcoming rural conflicts, and modifying

the agrarian structure.

William Quintero, DDR Manager – MAPP-OAS

Synthesis: The presenter commended the Victims’ Law and

the Land Restitution process for constituting significant public

policy advances and prioritising victims. However, insecurity and

community distrust towards government institutions constitute

critical challenges. Ongoing displacements, the re-victimization

of communities that are undergoing land restitution, and the

lack of clarity among government institutions on their roles are

also concerns. The use of front men to acquire lands, violently

or otherwise, poses further obstacles, particularly in areas where

post-demobilization groups are exerting force to protect illegally

seized properties.

1 “Rural Colombia: Reasons for Hope”, National Report on Human Development, UNDP,

Colombia, 2011.

Ivonne Moreno, Planning Coordinator of the Land Restitution

Program – Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development

Title: Land Restitution – Victims’ Law and Land Restitution,

Law 1448 of 2011

Synthesis: Forced displacement has historically been central

to the territorial configuration of Colombia. Approximately 55

per cent of IDPs abandoned or were dispossessed of their land,

resulting in 5.5 million ha (or 11 per cent of Colombia’s arable land)

in abandoned and now illegally held land. The Land Restitution

process seeks to guarantee the right of victims to have their

land properly titled and returned, and improve socio-economic

conditions in the rural sector. The government recognizes

significant challenges and risks in this process, and developed a

strategy to mitigate these by strengthening civil society.

Adriana Buchelli, Protection Officer - UNHCR Title: Challenges of Territory and Land Restitution Initiatives

Synthesis: Territory and land restitution initiatives face serious

challenges, particularly due to the ongoing-armed conflict. Special

attention must be paid to the risks of restitution processes,

and greater institutional capacity and protection measures are

required to mitigate them. In addition to protection measures

by the state, community development and protection networks

play an important role. Coordination between institutional and

international community initiatives should be enhanced.

Carlos Andrés Ramírez, Representative - Comisión de

la Sociedad Civil Vallecaucana para el Seguimiento a la

implementación de la Ley de Atención de Victimas 1448 de 2011 /

Corporación Nuevo Arcoíris

Synthesis: Civil society was late to the development of Victims’

Law, and has had limited representation in its implementation.2

Instead of viewing the law as a favor to victims, their rights to

justice, non-repetition and reparation must be guaranteed to

ensure community empowerment. The greatest challenge for

collective reparations is their sustainability (fulfilling guarantees

of non-repetition) and considering the multiplicity of parties

involved. In analysing the feasibility of implementation, we must

also take into account the corrosive role of drug trafficking in

public policy as evidenced in the political violence prior to the 2011

local elections.

Panel 3. Challenges for Humanitarian Action

Moderator: Gustavo Salazar – Universidad Javeriana

María José Torres, Head of Office – OCHA

Synthesis: Key challenges in the implementation of

Humanitarian Action include the invisibility of civilian needs;

the placement of checkpoints by armed actors, including

post-demobilization groups without clear political objectives

(denominated by the government as criminal bands, or “BACRIM”

for the Spanish acronym); presence of APM/UXO; assistance

for emergency prevention and mitigation; and discrimination

against vulnerable populations and subgroups. Implementation

of the land restitution process in the midst of an active conflict

may obscure ongoing humanitarian issues, including forced

displacement, massacres, and humanitarian access. Moreover,

the transformation of the government agency Acción Social

threatens to de-prioritise humanitarian assistance within the

agenda of Victims’ Law. Moreover, as 50 per cent of Colombia’s

rural population lives in zones of yellow and red alert for APM/

UXO presence, the restitution in these zones may result in more

victims of these devices. Greater CSR among economic engines

is important in order to address the impacts on natural resources

and the environment, as well as social conflicts and the armed

conflict.

2 CODHES makes a similar comment, stressing that the current version of Victims’ Law

did not undergo public consultations in order to incorporate proposals from victims’

groups. “De la seguridad a la prosperidad democrática en medio del conflicto”, CODHES

Informa, Número 78, Bogotá, 19 September 2011, p. 22.

Giovanny Cruz, National Coordinator of Humanitarian and

Emergency Affairs – World Vision Synthesis: The Victims’ Law must go beyond mere assistance in

order to facilitate life with dignity and engage civil society in early

recovery processes within a broader framework of humanitarian

action. Humanitarian organizations have a key role to play in

listening to communities and learning from them, in order to

help fortify existing capacities. Given that civil society offers the

first response to emergencies, humanitarian actors must build a

strong alliance with it. Finally, it is imperative to create academic

programs in order to further professionalise officials delivering

humanitarian assistance.

Luisa Bacca, Protection Officer – UNHCR, Nariño

Title: Permanent Humanitarian Mission in the Awá’s Indigenous

Territory

Authors: Protection Cluster - Gender Working Group - Nariño

Synthesis: The territory of the Awá indigenous people is located

in the departments of Nariño and Putumayo. This community

faces the threat of cultural and physical extermination due to the

ongoing-armed conflict, the lack of governance and institutional

support, and structural poverty. The Permanent Mission is

composed by UN agencies and international NGOs, and aims to

provide protection through their presence and by advocating for

the rights of the Awá people.

Ángela Sánchez, Coordinator of Southwestern Office – Oxfam

Title: Documentation of the experience of Gender

Differentiated Approach in Nariño department

Authors: Gender Working Group - Local Humanitarian Team –

Nariño

Synthesis: Women and their families in Nariño face special risks

posed by the armed conflict and a complex humanitarian context.

Some of these include individual and massive displacement,

child recruitment, pressure regarding illicit crop cultivation and

eradication, APM/UXO, confinement and mobility restrictions,

direct attacks and SGBV. The main objectives of the Gender Working

Group are to: mainstream the gender approach of humanitarian and

development projects; promote the implementation of effective

protection mechanisms for women; advocate for the assistance

HIV victims; further the development of new masculinities; and

communicate experiences of applying a gender differentiated

approach with indigenous and afro-descendent women in Nariño.

Regional Surveys

I. LA GUAJIRA/NORTH CESAR<ref />

Confrontation among non-state armed groups in the area is

related to control of drug trafficking routes, taking advantage

of ports in La Guajira and sparse border that both La Guajira

and northern Cesar share with Venezuela. According to Gerson

Arias, paramilitarism consolidated in the region during the 1990s

due to the tolerance of illicit activities by the Wayúu and other

local communities, the continuity of contraband and other illicit

activities by private armed actors, and the support or inaction of

civil and military authorities.2 Some mining executives came to

justify and support these structures due to attacks by ELN on their

infrastructure, hostile environment, and limited State protection.3

Post-demobilization groups are increasing their presence, partly

by rearming demobilized paramilitaries.

Armed groups have engaged in relatively selective violence

throughout the region, and crimes such as human trafficking,

small-scale drug trafficking and money laundering are key

concerns. The institutional capacity to investigate and prosecute

crimes by non-state armed groups and guarantee the protection

of civilians needs to be reinforced in order to combat impunity.4

Profound social distrust towards the public and private

sectors hinders the implementation of public policies and social

programs. This is exacerbated by the efforts of some officials to

discredit victims and obstruct justice, as was evidenced in the

proceedings regarding the killing of five civilians in June 2011, by

members of the Army in Cesar.5

Since the 1980s, 70,000 indigenous people have been displaced

in La Guajira and Cesar due to mining activities, particularly those

of El Cerrejón, the largest coal mine in Colombia.6 Also, mining

exploitation by Drummond in Jagua de Ibirico provoked a series

of displacements and illegal land appropriations, including in the

townships of Mechoacán and Prado. Similarly, there appear to

be forced displacements in Pueblo Bello and Valledupar, and in

neighbouring Sierra Nevada de San Marta. Carbon mining has

contaminated Rancherías River, the most important in Guajira,

triggering diarrhea and rashes among indigenous people who

depend on it.7 Repopulation strategies have resulted in complex

situations, given the leadership of armed groups and mafias

that have coopted processes through political infiltration and

corruption. Consequently, some displacements between Dibulla

and Riohacha, attributed to the post-demobilization groups

Rastrojos and Urabeños, have gone unreported. In the El Copey

zone, displacements and forced sales have taken place for palm

cultivation. Combats between the army and the FARC have

resulted in three massive displacements in El Perijá.

Mining expansion projects throughout the region, strip mining

in Perijá Mountains and the diversion of Ranchería River for coal

exploration have all had a significantly negative environmental

impact and enhance the local population’s vulnerability to

disasters of natural origin.

Civil society is reportedly becoming weaker and more

fragmented, affecting most local ethnicities and inhabitants.

Moreover, illegal surveillance, threats against and murders of

union and community leaders in Cesar is hindering local capacity

to provide social mobilization and advocacy.8 Land use is heavily

determined by the territorial control of non-state armed groups,

which is currently being disputed in urban areas of central and

northern Cesar. A non-state armed group, calling itself “Wayúu

counter-insurgency front of Alta Guajira”,9 is responsible for a

series of massacres10 and is feeding inter-ethnic conflicts tied to

retaliation traditions.

The interaction between paramilitary networks and politicians

(“parapolítica”) persists in La Guajira without the visibility and

political restructuring that took place elsewhere in the country.

Traditional political networks remain unaltered and illegal

networks continue to operate under the control of political elite

families, thus hindering human rights work. In contrast to other

regions, Cesar experienced a change in political power and the

victims’ agenda became a priority thanks to the pressure placed by

civil society organizations. Nevertheless, effective sustainability

and a long-term strategy do not appear feasible.

Despite the existence of significant humanitarian crises,

regional experts stress the very limited presence of humanitarian

actors in the region.

1. While the regional statistics and map refer to the departments of Guajira and Cesar

as a whole, the information below focuses on conflict and humanitarian dynamics in

Guajira and the northern region of Cesar.

2. Arias, Gerson, “Pasado y Presente del entorno de seguridad en La Guajira”,

Fundación Ideas para la Paz and VerdadAbierta.com, Bogotá, 27 October 2010,

Presentation at Event.

3. Reyes Posada, Alejandro. 2008. Guerreros y Campesinos: El despojo de la tierra en

Colombia. Bogotá: Fescol, Grupo Editorial Norma, p. 208.

4. As asserted by UNHCHR, impunity is a “structural problem affecting the full

enjoyment of rights.” “Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human

Rights on the situation of human rights in Colombia”, UNHCHR, 31 January 2012.

5. Some Army officers continue to deny extrajudicial executions, including “false

positives”, instead discrediting the justice system and victims. UNHCHR, 2012, p. 8.

6. “Minería en Colombia: ¿a qué precio?, Boletín informativo no. 18 PBI Colombia”,

Peace Brigades International, Bogotá, November 2011, p. 32

7. Ibid.

8. UNHCHR, 2012, p. 5.

9. Notorious paramilitary Jorge 40 allied with José María Barros Ipuana and José María

Gómez to establish this front, but resistance by traditional indigenous structures has

been fierce and sometimes violent. “Dinámica Reciente de la Confrontación Armada

en la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta”, Observatorio de Derechos Humanos de la

Vicepresidencia, February 2006.

10. The massacre on April 18, 2004 in Bahía Portete (Guajira) was a targeted attack

on women with profound implications on a relatively populous, but historically

threatened, indigenous minority. It simultaneously exemplifies the highly functional

use of violence against women, and the role of deep-seated institutional and societal

discrimination against marginalized communities. The massacre not only threatened

the historical, cultural and mythical patrimony of the community, but also its ethnic

survival. “La Masacre de Bahía Portete: Mujeres Wayuu en la mira”, CNRR, Bogotá,

2010.

II. NORTE DE SANTANDER

The Department has a geostrategic location, which has made it a key corridor for drug and human trafficking, as well as arms and fuel smuggling. The high presence of non-state armed groups and criminal organizations in the border areas create security risks that impact the civilian population and exacerbate humanitarian needs. Over the past two years there have been massacres, homicides, kidnappings and human trafficking throughout the zone.1

The end of the armed conflict in the region remains elusive, particularly taking into account the intensity of the armed conflict along the border with Venezuela. Non-state armed groups and criminal organizations have reportedly formed alliances to exploit drug trafficking. Manual drug crop eradication processes take place throughout the Catatumbo area of Norte de Santander, leading to constant protests, armed confrontations and an increase in the use of landmines. These events lead to displacement risk and affect local food security.2

Children and teens are vulnerable to recruitment by illegal armed groups, particularly in Catatumbo and the Cúcuta Metropolitan area, and prevention policies need to be further developed and implemented. There are two reports of threats by the FARC to recruit 7-year-old boys.3 There are periodic trainings and minors reportedly participate in isolated operations. The Motilón-Barí community is considered to be an indigenous community at high- risk due to the conflict.4 Another concern is human trafficking, as well as high SGBV and HIV/AIDS rates among IDPs.

In 2010, armed actions increased to 62 reported events related to the armed conflict, compared to 47 in 2009. During 2010, 27 out of the 40 municipalities, representing 67.5 per cent of the Department, were affected by armed or violent actions related to conflict.5 According to the local NGO Progresar, there were 60 reported cases of forced disappearance in 2010, 90 per cent of which were concentrated in the municipalities of Cúcuta and Villa del Rosario.6 Since 2008, Human Rights and IDP organization leaders have reported numerous threats.7 Non-state armed groups have threatened former government employees and candidates to public office.

The threat of displacement is mostly individual, though there are risks of mass displacement in areas such as Catatumbo. In 2010, the accumulated number of IDPs reached 79,851 expelled and 101,654 received. There is an under-registry, with a high percentage of ‘non-inclusion’ of IDP declarations on the part of former Acción Social, including non-registry of “inter-vereda”

28 (rural displacement within a municipality) or inter-urban displacement, which cannot be declared according to Law 387 or are invisible; flight to other regions or across the Venezuelan border.

The 2010-2011 rainy season left a total of 61,746 persons affected in Norte de Santander, and caused flooding and landslides in 80 per cent of Department. The Gramalote municipality was entirely destroyed and must be re-located due to geological fissures. During 2011, the local authorities reported 3,321 new families affected by the rainy season. While adults consumed three daily food rations, children consumed just two.8 The WFP delivered 8,249 food rations to 2,749 families, 13,745 people. The National Response Organization Colombia Humanitaria has given monetary resources to respond to the needs identified on food, shelter and sanitation.

The rainy season also led to the collapse of 71 per cent (1,017 of 1,436km of roads) of the secondary road system, including the road infrastructure connecting the capital, Cúcuta. This resulted not only in the isolation of the capital, but also in constraints for humanitarian access.

APM/UXO presence also hinders access and mobility, not only for the local population, but also for humanitarian organizations. In 2010 there were 43 APM/UXO events, killing one civilian and 31 military personnel. The Department has among the top five numbers of victims of these devices in Colombia. The risk is exacerbated as guerrillas use these devices in their attempt to block the entrance of manual eradicators of coca crops in their zones of influence.

1. Information provided by regional field office, OCHA, May 2011.

2. Information provided by regional field office, OCHA, May 2011.

3. UNHCHR, 2012, p.14.

4. Information provided by regional field office, OCHA, May 2011.

5. Information provided by regional field office, OCHA, May 2011.

6. Report on Human Rights in Norte de Santander: Right to Life and Physical Integrity, National NGO Progresar, 2012.

7. Special Report on the increase of “False Positives”, Centro de Investigación y Educación Popular (CINEP), 2011.

8. Report on Food Security, regional field office of the World Food Program, 2011.

III. BOLIVAR (MONTES DE MARIA)

Montes de María has historically been treated as a “laboratory”, combining the implementation of the National Consolidation Plan, the Victims’ Law and Land Restitution, rural resident reserve and rural development areas. The zone also presents all major actors of the armed conflict, each with a territorial control exercised over a certain part of society.1

The military is building capacity among youth for the prevention of forced recruitment and child exploitation, as well organizing communities around the land restitution process. It is of concern that the government remains silent regarding numerous IHL infractions and IHRL violations in the zone.